Origins and Role in East Asian Culture

Go, or Weiqi in Chinese, originated in China over 2,500 years ago and is considered one of the oldest board games still played today. Traditionally ranked alongside the guqin, calligraphy, and painting as one of the “Four Arts” of the scholar, Go has been deeply embedded in the intellectual, artistic, and philosophical life of East Asia. In China, Japan, and Korea, Go has served not only as entertainment but also as a tool for cultivating patience, strategic thinking, and moral character.

Global Spread and Modern Popularization

While Go has long been popular in East Asia, its global recognition surged in the 21st century. Two cultural phenomena played a major role: the Japanese manga and anime Hikaru no Go, which introduced Go to a new generation of players worldwide, and the rise of artificial intelligence, particularly the 2016 matches between Google DeepMind’s AlphaGo and top professional Lee Sedol. These events captured international attention, inspiring many newcomers to learn the game and sparking discussions on strategy, human creativity, and technology.

Go in Film

Go has long been a favorite cinematic device, symbolizing strategy, balance, and the meeting of minds. In film, the black-and-white stones often stand in for the quiet intensity of intellectual or emotional battles.

Go in Cinema Compilation (2025) – Premiered at the Opening Ceremony of the 2025 American Go Congress, this special video highlights iconic Go moments in cinema, blending East Asian classics with global storytelling.

Pi (1998) – Darren Aronofsky’s psychological thriller uses Go to represent the search for universal patterns in mathematics, nature, and human behavior.

A Beautiful Mind – “The Challenge” (2001) – In this Academy Award–winning biopic of mathematician John Nash, a tense Go game between Nash and a rival student serves as a silent intellectual duel, foreshadowing the film’s deeper themes of competition, genius, and perception.

Hero (2002) – In Zhang Yimou’s historical epic, a Go match between two characters unfolds against the backdrop of an assassination plot. Each deliberate move mirrors the story’s intricate political strategies.

Go Documentaries

While Go has a rich history in fiction and cinema, it has also been the subject of numerous documentaries that explore its culture, history, and human stories. These works provide valuable insight into how the game shapes lives and connects communities worldwide.

The Surrounding Game (2017)

Directed by Will Lockhart and Cole Pruitt, both avid Go players in the United States and graduates of Brown University.The two were inspired by the growing movement to promote the game outside East Asia.

The documentary follows the journey of top young American Go players—including Andy Liu, Ben Lockhart, and others—as they train, compete, and immerse themselves in the international Go scene. It also features interviews with legendary figures like Cho Hunhyun, Go Seigen, and Michael Redmond.

AlphaGo (2017)

Chronicles the historic matches between DeepMind’s AlphaGo AI and world champion Lee Sedol, capturing the tension, excitement, and philosophical questions raised by artificial intelligence surpassing human skill in Go.

Go Through the Dark (2021)

Directed by Yunhong Pu, Go Through the Dark follows Guanglin, an eleven-year-old blind boy from China who demonstrates remarkable skill in the ancient board game of Go. Raised by a single father, Guanglin must navigate societal prejudice and immense pressure as he pursues his talent in a domain dominated by sighted players. The film won early recognition as a world premiere entry in the International Competition at DOC NYC (2021)

Go as a Strategic Metaphor

For centuries, the game of Go (weiqi in Chinese) has been more than just a pastime in East Asia—it has served as a model for thinking about competition, strategy, and the exercise of power. Unlike chess, where the goal is to eliminate the opponent’s king in a direct and decisive strike, Go rewards patience, adaptability, and the gradual accumulation of influence. Its core principles—encirclement, multi-front engagement, and balance between attack and defense—have inspired analogies in diplomacy, military planning, and even corporate strategy.

This section explores how Go has been used as a metaphor for strategy in different contexts. From Henry Kissinger’s reflections in On China to David Lai’s military analysis, and through journalistic perspectives in The Economist and The Globe and Mail, these interpretations reveal how a 2,500-year-old board game continues to shape the way people understand global power and negotiation.

Kissinger – On China

Henry Kissinger (1923 – 2023) was a German-born American diplomat, political scientist, and Nobel Peace Prize laureate. Serving as U.S. National Security Advisor (1969–1975) and Secretary of State (1973–1977), he played a pivotal role in shaping American foreign policy during the Cold War, most notably in opening diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China in the 1970s.

In On China, Kissinger contrasts Western and Chinese strategic traditions through chess and Go, respectively. He writes that Go (“Wei-qi” in Chinese), literally “a game of surrounding pieces,” emphasizes encirclement and flexible positioning rather than direct confrontation. This metaphor illustrates how Chinese diplomacy often favors gradual, indirect influence—shaping outcomes through multi-front maneuvering rather than decisive, head-on victory.

David Lai’s Learning from the Stones: Military and Strategic Insights

David Lai, a scholar at the U.S. Army War College Strategic Studies Institute, published his influential 2004 monograph Learning from the Stones: A Go Approach to Mastering China’s Strategic Concept, Shi. In this work, Lai contends that Go is far more than a recreational game—it is a “living reflection” of Chinese philosophy, military strategy, and diplomatic practice.

Since its publication, Learning from the Stones has had significant influence in both academic and policy circles. It has been cited in Military Review, strategic studies journals, and U.S. military training materials as a key framework for interpreting China’s actions in the so-called “grey zone” of competition—areas where rivals can suffer setbacks in some arenas while achieving gains in others, such as technology, trade, and regional influence. The work has also been referenced in think tank briefings and international relations courses, reinforcing its status as a seminal text linking an ancient board game to modern strategic thinking.

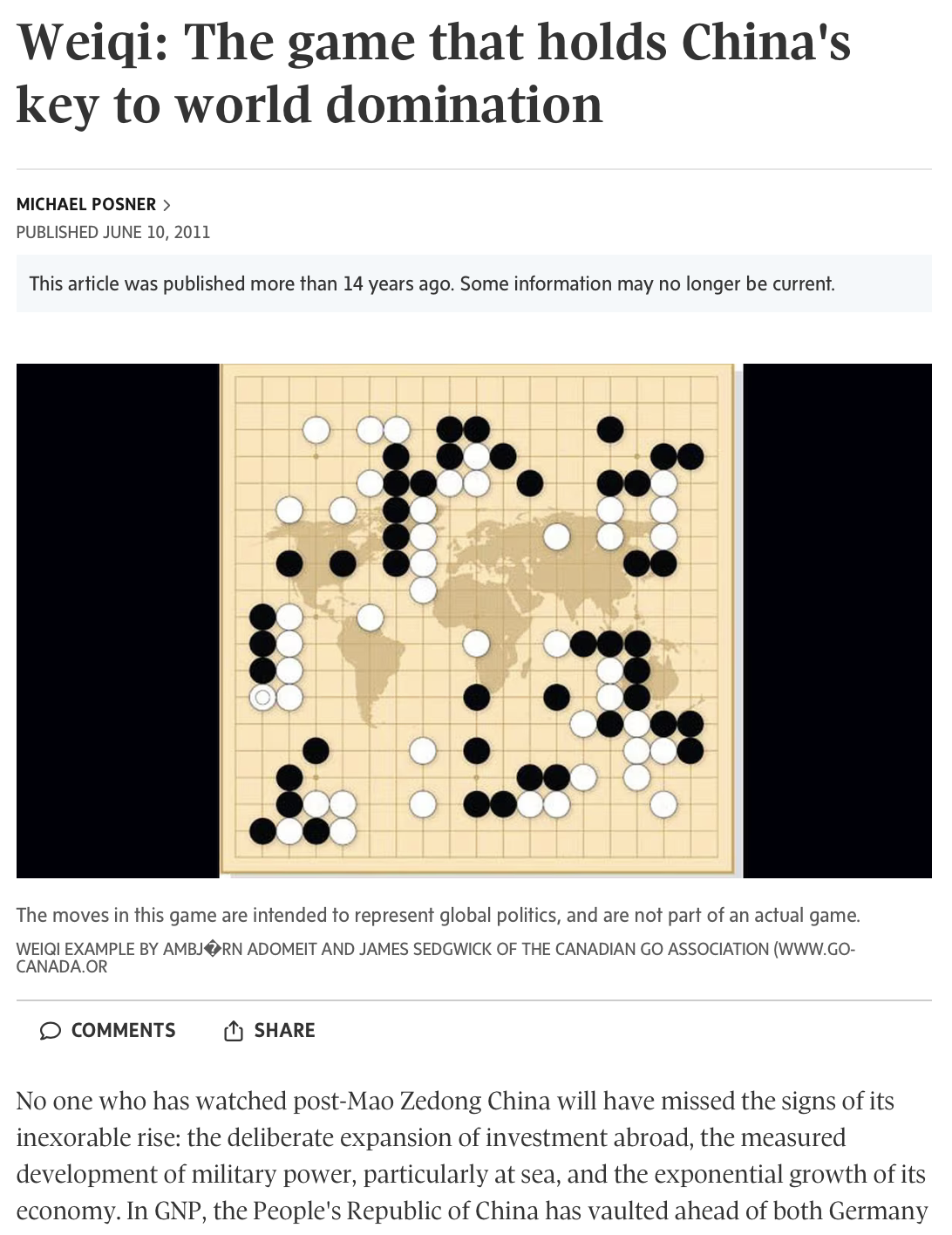

The Globe and Mail — Go as China’s Strategic Key to Global Influence

In the June 2011 opinion piece “Weiqi: The Game That Holds China’s Key to World Domination”, Michael Posner uses the ancient board game weiqi (Go) as a metaphor for China’s long-term geopolitical strategy. Unlike chess, which focuses on quick, decisive victories and head-on confrontation, weiqi emphasizes gradual territorial encirclement, patient positioning, and the indirect accumulation of advantage.

Posner links this mindset to Chinese foreign policy, noting how it manifests in initiatives such as the “one country, two systems” approach to Hong Kong, influence campaigns toward Taiwan, overseas investments in Africa and South America, and the Belt and Road Initiative. These actions, he argues, mirror Go’s philosophy of expanding influence without triggering direct conflict.

The article contrasts this with Western strategic thinking—often more like chess—characterized by rapid, zero-sum clashes for dominance. By comparison, China’s Go-inspired approach is incremental, adaptive, and rooted in centuries-old cultural and philosophical traditions.

The Economist — Go as a Geopolitical Metaphor

In November 2021, The Economist published the article “How the game of Go explains China’s aggression towards India”. It examined the Sino-Indian border standoff and used Go as a metaphor for China’s gradual, positional strategy:

China was portrayed as methodically extending control in contested zones, similar to Go’s “encircling territory” tactic.

This approach is not purely zero-sum; rather than aiming for outright annihilation, it accumulates influence in key areas to shape the overall balance of power.

“Go teaches that small territorial gains can matter far more than flashy, short-lived tactical victories.”